The Caesar Roman civil war is one of the those times in history when an abrupt change can be studied and looked at closely.

Many people in modern times often look to the Roman civil war and try to relate it to current events.

This can be problematic since there was so much was happening at the time anyone can find a story to fit their narrative.

Most will look at the many battles Caesar fought with Pompey and other such as Labienus and Scipio in North Africa.

While the battles are what interest most people the politics in Rome and the aftermath of the civil war is also very interesting.

One major thing to note is when the war started, with Caesar crossing the Rubicon, his main lieutenant and second in command was a man called Labienus.

Labienus was Caesar’s go to lieutenant for 10 years in Gaul and had never lost a battle while leading the legions.

He also was in charge of governing Gaul while Caesar was away.

When Caesar marched on Rome and crossed the Rubicon it was a great surprise to Labienus who was not consulted.

Labienus left the legion on Gaul and joined Pompey and the Senate against Caesar.

This was a great loss for Caesar who was forced to rely on a less accomplished lieutenant Mark Anthony.

Mark Antony was a good soldier and remarkably loyal but left a lot to be desired as a leader.

After marching on Rome Pompey and the Senate fled to Greece which Caesar had to chase.

Before leaving he left Mark Antony in charge of Rome with one Legion.

Mark Antony leadership while watching Rome was not good.

One of the first problems he had was a movement to abolish debts.

Debt was a very real problem for the poor people of Rome with the rich upper class owing the debt.

The poor obviously wanted the debt erased while the rich upper class wanted it to be payed back with interest.

A tribune attempted to push a bill through the Senate that would of abolished the debts.

The Senators most of who where part of the rich upper class were against the bill and blocked it.

That should have been the end of the whole thing, but instead, the Tribune started going around making impassioned speeches in front of growing crowds.

Before too long, he was able to lead an angry mob into downtown Rome and occupy the Forum.

This tactic of taking to the streets wasn’t totally unprecedented, but the speed at which Rome’s political class lost control of their city was alarming to say the least.

This was a problem but it was a problem with an clear solution, right?

Antony was in charge and had an army sitting just outside the pomerium, so obviously he would cross the pomerium and lead the army away from the city.

Hold on, he what?

Yeah, he turned the city over to the angry mob.

Do you think this is what Caesar had in mind when he left the city in Antony’s hands?

I imagine not.

The likeliest explanation for this is that he wanted to send a message.

The Senate had become really bent out of shape when Caesar left Antony in charge.

So much so that they actually tried to get him removed.

Antony was, uh, petty?

Now that the city was in trouble, he wanted the Senate to beg him to intervene.

But things didn’t quite go as he expected.

The situation deteriorated quickly.

The mob began to openly bring weapons across the pomerium, which was illegal, but who was going to stop them?

They eventually started launching deadly attacks against their perceived enemies.

Rome’s political class became afraid to be seen in public. The city was basically ungovernable.

Under armed guard, the Senate met at an undisclosed location and passed the Senatus Consultum Ultimum, or the Final Act.

This legislation empowered the consuls to do “whatever necessary” to defend the Republic.

It’s important to note although the Senate clearly had a plan, there were currently no consuls in office, and so it’s hard to see how any of this would stand up in court.

But before any plan could materialize, Antony returned in force and marched right across pomerium with several armed cohorts.

The soldiers descended on the mob with swords drawn, and hundreds of Roman citizens were killed.

This was the apex of pettiness.

Antony deliberately allowed the situation get out of control and then needlessly butchered a bunch of Roman citizens.

If Antony was disliked before, he was despised now.

When the Senator Cicero arrived back in Italy after the Pompeian defeat at the Battle of Pharsalus, a letter arrived from Antony telling him that he could not guarantee Cicero’s safety, and that it would be best if he stayed away from Rome for a while.

This was highly irregular.

Cicero was one of Rome’s most influential politicians, and in case you missed it, this was a threat.

Why?

Because Antony didn’t like Cicero, that’s why.

This blatant and unnecessary abuse of power hardly improved the Senate’s opinion of Antony.

But hang on, because it was about to get a lot worse.

For starters, Antony just straight up stole Pompey’s giant mansion in the center of Rome.

One day it was empty, and the next day Antony had moved in.

This was a giant red flag because a generation earlier, the last Civil War had ended with the winning side murdering a bunch of Senators and stealing their property.

Caesar had promised that this Civil War would be different, but with Antony doing stuff like this people weren’t so sure anymore.

Antony’s behavior quickly got out of hand.

He would show up to Senate meetings blind drunk, or would disappear for days at a time on wild benders.

There’s one account that says that after butchering hundreds of Roman citizens, Antony thought that it would be a good idea to be carted around the city like a triumphal general in a chariot pulled by lions.

This whole thing was made 10 times worse with the fact that nobody had heard from Caesar in like 6 months.

People began to fear the worst.

Some whispered that with Caesar out of the picture, they may have to take this Antony problem into their own hands.

But Cicero was hopeful.

He reassured his allies, writing: “It seems to me that though Caesar is holding Alexandria, he is ashamed to send a dispatch on the operations there.”

Cicero was exactly right.

A couple of months later Caesar defeated the Egyptian army at the Battle of the Nile, bringing the Siege of Alexandria to an end.

After a brief detour to Asia Minor, the Senate received word that Caesar would be returning to Italy.

The political class in Rome breathed a collective sigh of relief.

When Caesar landed in Italy, Cicero was there to meet him.

When they saw each other, Caesar ran up and gave Cicero a big hug.

As the reunion traveled inland, the two men hung back from the group and spent several hours lost in private conversation.

I imagine Antony’s name came up once or twice.

Caesar made a point of avoiding Rome for the time being.

He wouldn’t be staying for very long anyways since the Civil War was still ongoing.

This was just a quick pit stop to raise new armies and then he was off again to North Africa.

But he was still politically engaged, and when he received a full report from his allies back in Rome, he as not pleased.

Antony was unceremoniously fired.

Caesar had his allies in Rome call for elections for the coming year.

Caesar was unsurprisingly elected consul en absentia.

This was against the rules, but rules were mattering less and less as time went on.

His consular colleague for that year would be a politician named Marcus Lepidus who was a good administrator and a skilled politician.

When Caesar went off to Spain at the beginning of the Civil War, Lepidus had overseen Italy without incident.

After Caesar’s victory in Spain, he picked Lepidus to serve as one of Spain’s new governors.

As governor, Lepidus surpassed all expectations.

While Caesar was away, a medium sized rebellion flared up.

Lepidus moved quickly and was able to defuse the whole situation without losing a single man.

This was exactly the kind of gumption that Caesar was looking for.

Unlike Antony, Lepidus didn’t need any adult supervision.

When Caesar tapped Lepidus to be his co-consul for the year 46, he unmistakably became Caesar’s new #2.

It’s worth noting that Antony, who a second ago had been the most powerful man in Italy, would hold no elected office.

The Senate then turned to Caesar and named him Dictator for a year.

The Dictatorship was an emergency measure that temporarily gave a person absolute control over the Roman military as well as the ability to override political vetos.

This would give Caesar plenty of leeway to wrap up the Civil War.

The office of Dictator came with a deputy, who was called the the Master of the Horse.

Caesar nominated his co-consul Lepidus as his Master of the Horse, and empowered him to act on his behalf while he was on campaign in North Africa.

For Lepidus, this was a massive vote of confidence.

Consider for a moment the pickle that Caesar was in as he prepared to leave for North Africa.

His regime had never been more unpopular.

On one hand he couldn’t really afford to spend any extra time or money in Italy, but on the other hand any further political deterioration might be catastrophic.

The plan that Caesar came up with here is just so next level, you just have to step back and marvel at it.

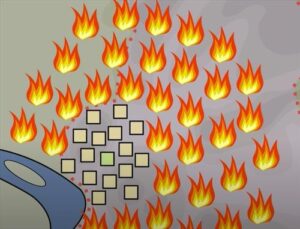

The big hot button political issue of the day was the movement for the abolition of debts.

We’ve talked about this.

It was the justification for the recent street violence, and it was quickly becoming the rallying cry for anybody opposed the status quo.

Caesar injected himself into this debate by sending his agents to all over Italy to the small and medium sized cities that dotted the Italian countryside.

These agents asked for meetings with the local aristocracy and then, on Caesar’s behalf, asked to borrow mind boggling sums of money.

War was bad for business, they said, and this loan would help Caesar bring an end to hostilities.

When that was done, Caesar turned around and published a bunch of pamphlets in Rome that said something like: “Debt abolition would be awesome, but as Rome’s richest AND most indebted citizen, it would benefit me most of all! It wouldn’t be fair!”

This was one hell of a switcharoo.

Not only did public enthusiasm for debt abolition instantly dry up, but it no longer made sense for Caesar’s political rivals to rally behind a policy to which Caesar would be the chief beneficiary.

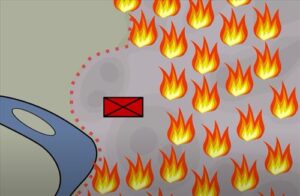

But here’s the really genius bit.

It’s a bit of a long walk, so pay attention.

Every year, 20 new politicians gained lifetime membership to the Roman Senate.

These politicians were the people who had just been elected Quaestor.

Quaestors were elected through a body called the Tribal Assembly.

Now the Tribal Assembly was sharply skewed – in today’s terms you might say gerrymandered- in favor of rich people from the Italian countryside at the expense of poor people from the city of Rome.

And what do we know about rich people from the Italian countryside?

They had all loaned Caesar all of their money.

What did this mean?

It meant that every candidate for Quaestor had to answer a very simple question from the most powerful part of their electorate: “are you going to help Caesar end the Civil War?

Yes or no?”

With this one move, not only did Caesar defang the movement for debt abolition, but he established a new set of political incentives that churned out an annual crop of young senators that basically shared his policy goals.

Or at least pretended to.

It really was an inspired bit of business.

When Caesar departed for North Africa, he left behind a Rome that was under new management.

Unlike Antony, Lepidus took his job seriously, and was careful not to alienate the Senate any more than absolutely necessary.

After some pretty lengthy delays due to weather, he was able to send four additional legions to North Africa, which played a pretty big role in Caesar’s eventual victory over the Pompeians at the Battle of Thapsus.

But Lepidus’s competence couldn’t fix Rome’s underlying problems.

For years, whenever Caesar had been faced with a difficult political problem, his response had been the same. “After the Civil War.”

Well, the Civil War was now over.

When Caesar returned to Rome in the summer of 46, he faced an angry populous; an embittered political class; a disgruntled military; and oh yeah, a truly ludicrous amount of personal debt.

To make matters worse, the Civil War had proven that Rome’s political system was thoroughly broken.

This was now Caesar’s problem, and it would prove to be intractable.

Here is a full Documentary about this time period in Rome.